True Translation

Translation was such an integral part of Flusser’s writing practice that it seems intrusive to translate again, or to translate what he did not. He was not in any way reassuring about the issue either: “…I believe that the only ‘true’ translation is the one attempted by the author of the text to be translated,” he wrote in “The Gesture of Writing.” That essay exists in seven versions, in four different languages (Guldin 2005, 280), including English. It is probably not a coincidence that it is the most extensive example of Flusser’s own pattern of translating his texts into others of the four languages he used (Guldin 2005, 88) and, sometimes back again. His purpose in doing this was, as he said repeatedly, to “exhaust” the thoughts that initially gave rise to the writing. Even his translation process, it would seem, aspired less to accuracy than to a controlled expansion or completion of a particular thought.

By Flusser’s own criteria, then, no contemporary translation can be “true,” for the simple reason that none of us can be Flusser. Accordingly, to translate his work at all one must either accept a judgement of inevitable “failure” or, on a happier note, abandon the ideal of a “true” translation altogether. In my view, the overall pattern of Flusser’s life and work argues most eloquently for the latter option. Faced with permanent exile from anything he could call “home,” the utter destruction of his former life and connections, the complete impossibility of engaging with the institutions that normally support a European intellectual, he effectively abandoned the ideals of “home” and “tradition” — even the search for “truth” as the goal of philosophy — and went on to construct a new, creative life out of the ruins.

The new ideal was one of creative, dialogic connection with others. This is what I would hope new translations of Flusser’s work could achieve. He himself described the issues with extraordinary clarity and grace: any language constructs a particular pattern of thinking or, as he would probably have said, a particular “universe.” A translator negotiates the treacherous, yet potentially creative gaps between them. We no longer have access to the range of associations Flusser himself made with the words and patterns of the languages he knew, the materials available to him for writing and translating his own texts. Contemporary translators cannot “mine” his ground. We can–we must–use our own.

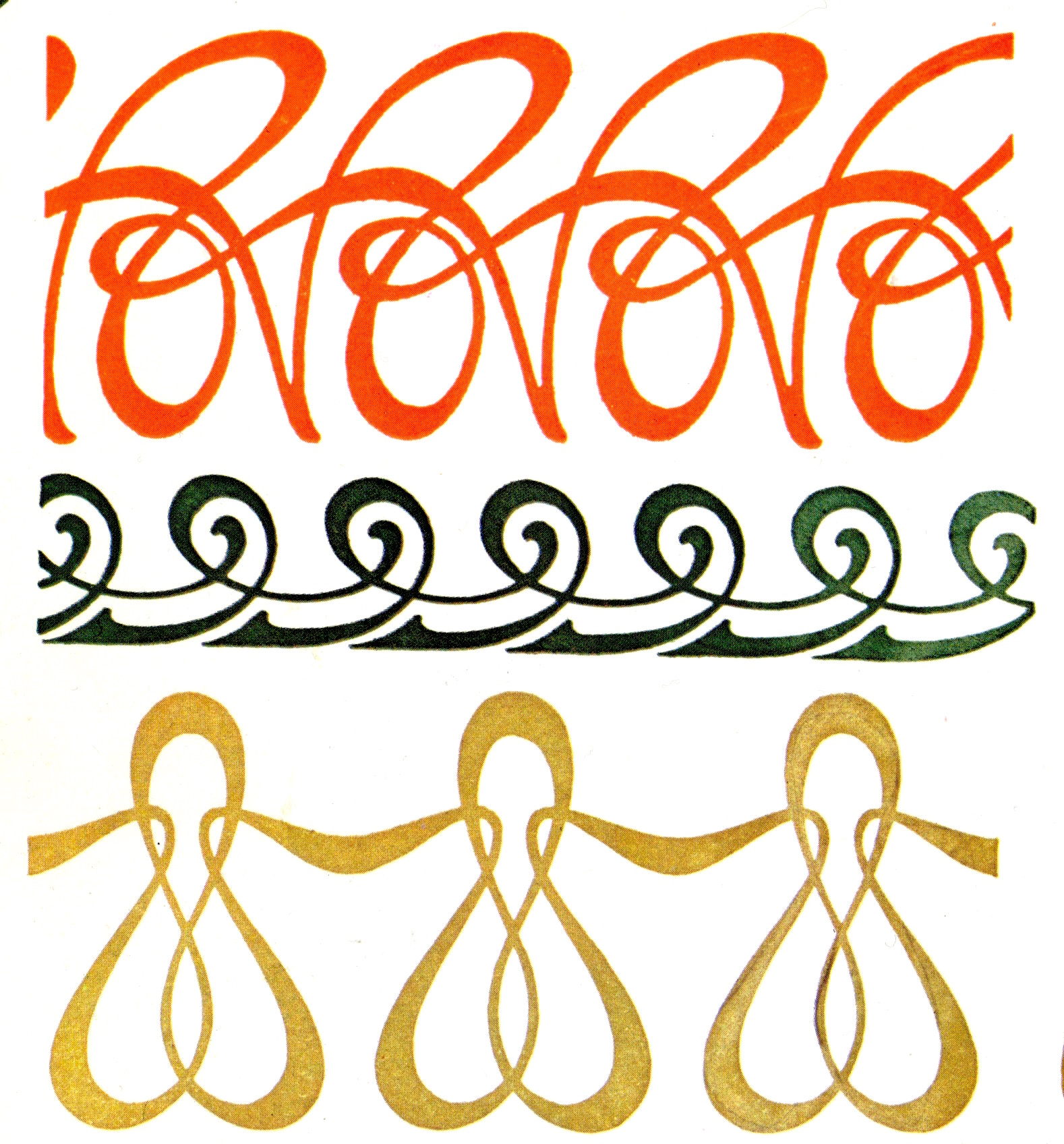

The image is a detail from a design by Alphonse Mucha (1860-1939).